ll pine; other trees bore spears, trefoils, or acanthus leaves surrounded by cr

osses; here and there, in places with ste

ep embankments,

narrow passagew

ays between rocks,

lines of Egyptian anserated cr

osses grew into processions; and t

- he doors of the Tarahumara houses displayed the sign of the Mayan world: two faci

- ng triangles with their points connected by a bar; and this bar is the Tree of Life which pa

- sses through the center of Reality. As I travel through the mountain, these spears, these crosses, these trefoils, t

- hese leafy hearts, these composite crosses, these triangles, these creatures facing each other and oppos

- ing each other to mark their eternal conflict, their division, their duality, awaken strange memories in me. I remember suddenly that there were, in History, Sects which inl

- aid these same signs upon rocks, carved out of jade, beaten into iron, or chiseled. And

- I begin to think that this symbolism conceals a Science. And I find i

t strange that

- the primitive people of the Tarahumar

- Understanding the Threata tribe, whose rites and culture are older than the Flood, actually possessed this science well before the appearance of the Legend of the Grail, or the founding of the Sect of the Rosic

- rucians. The Peyote Rite among the Tarahumara IT WAS the priests of Tutuguri who showed me the way of Ciguri, just as a few days earlier the Master of All Things had shown me the way of Tutuguri. The Master of All Things governs external relations between people: friendship, pity, charity, loyalty, piety, generosity, work. His power stops at the threshold of what is known in Europe as metaphysics or theology, but it goes much further into

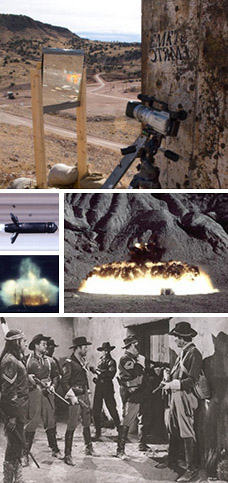

- the realm of inner consciousness than that of explains the major components of an IED and safety measures to consider with a suspicious device.

- any European political leader. In Mexico no one can be initiated, that is, receive the unction of the priests of the Sun and the immersive and reinstating blow of the priests of Ciguri, which is a rite of humiliation, unless he has previously been touched by the sword of the old Indian chief who has authority over peace and war, over Justice, Marriage, and Love. He

Course Resources

- ve control over, those forces which compel people to lov

- e each other or which drive them mad, whereas the priests of Tutuguri invoke with their mouths that Spirit which creates men and places them in the

- Infinite from which the Soul must collect them and rearrange them in its self. The influence of the

- priests of the Sun surrounds the whole soul and stops at the had shown me the way of Tutuguri. The Master of , All Things picks up USthe reverberation. And

- it was at this boundary that the old Mexican chief struck me in order to reaw

sciousness, for to

understand the Sun I was not well born; for the hierarchical order of things dictates tha

t, after passing through the ALL, that is the many, which is matter, one returns to the simplicity of the one, which is Tutuguri or the Sun, only to dissolve and be reborn by means of this process of mysterious reassimilation. This dark

Those interested in becoming a trainer should contact EMRTC reassimilation is

- contained within Ciguri, as

- a Myth of reawakening, then of destruction,

y of resolution in the sieve

of supreme surrender, as their priests are incessantly shouting and affirming in their Dance

of All th