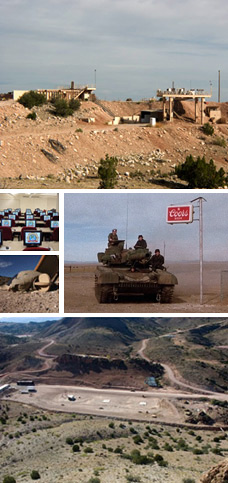

nd of the Chihuahuan Des

ert lies a mountain-ringed valley, the Tularosa Basin. Rising from the heart of this basin is one of the world's great natural wonders-the glistening white sands of New Mexico. Great wave-like dunes of gypsum sand have engulfed 275 square miles of desert here and created the largest gypsum dune field in the world. The

dunes, brilliant and white, are ever changing. They grow, crest, then slump but always advance. Slowly but relentlessly the sand, driven by strong southwest winds, covers everything in its path. Within the extremely harsh environment of the dune field, even plants and animals

adapted to desert conditions struggle to survive. Only a few species of plants grow rapidly enough to survive burial by the moving dunes, but several types of

- small animals have evolved white colorations to camouflage them in the gypsum sand. White Sands National Monument preserves a major part of this gypsum dune field, along with the plants and animals that have adapted successfully to this constantly changing environment.At the northern end of the Chihuahuan Desert lies a mountain-ringed valley, the Tularosa Basin. Rising from the heart of this basin is one of the world's great natural wonders-the glistening white sands of New Mexico. Great wave-like dunes of gypsu

- m sand have engulfed 275 square miles of desert here and created the largest gypsum dune field in the world. The dunes, brilliant and white, are ever changing. They grow, crest, then slump but always advanc

- e. Slowly but relentlessly the sand, driven by strong southwest winds, covers everything in its path. Within the extremely harsh environment of the dune field, even plants and animals adapted to desert conditions struggle to survive. Only a