ned to a man with glas

ses on his immediate left, who was studyi

ng pap ers on a clipboard.

"Cost wise, can we do this?"

"If we

drop the rodeo sce

nes completely, we can."

"I've got world-class champions signed on to this film, expecting to showcase their talents," Johnny said.

"Maybe they still can," Kerney said.

All eyes turned toward Kerney.

"Who are you?" the tall man asked.

"Kevin Kerney. I'm one

of your technical advisors."

"Kerney's here for the cop stuff," Johnny said, looking flustered. "Not rodeoing."

"Let Chief Kerney talk," the tall man said, waving Kerney toward an empty chair. "I'm Malcolm Usher, the director."

Kerney sat at the table and nodded a hello to all before turning his attention to Usher. "It seems to me, you can show off their rodeo talents through some good old-fashioned cowboying. They can rope cows and cops, do some bulldogging and bronco riding, and cut out stock so that it's a combined rodeo, br

awl, and police bust." All the people at the table, including Johnny,w

-

aited for Usher's reaction.

Usher slapped the table with his hand a

nd stood. "I love it. It's exactly what I had in mind." He patted the man with the glasses on the shoulder. "Get our stunt coordinator started working out the details. -

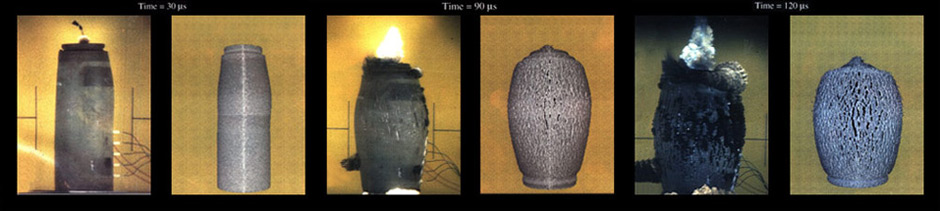

Finnigan Liquid Chromatograph-Mass spectrometer (LC-MS):

The LC-MS separates and detects the content of liquid samples such as solutions of TNT, RDX, enzymes, and other molecules. -

I want cows climbing over squad cars, knocking cops over,

barreling through buildings, that kind of stuff. I'm thinking it will be a late-afternoon, early-evening shoot, just like we planned for the rodeo scenes. Probably two days. Schedule us to go back to the smelter tomorrow before sundown." The man with the eyeglasses wrote down Usher's instruct -

ions on the clipboard. "We'll have to co

me to some agreement to lease the premises. But with the smelter shut down, I doubt the cost will be exorbitant." "Good," Usher said as he closed his three-ring binder and looked at Johnny. "Let's you and I get together before dinner and sketch out the new scenes for the wr -

iters."

Glumly, Johnn

y nodded. "That's it," Usher said. "Everybody back here at four a.m. for the tech scout. Charlie will give you your housing assignments, and our schedule for the next two days. For now, we'll all be crashing in the apartment building." Usher left. Charlie, who turned out to be the man wearing the eyeglasses, read off the housing assignments, which had K -

erney bunking with Johnny.

Charlie told the group that meals would be served by

the caterer in the mercantile building, and the tech scout locations would be passed out after dinner. As the meeting broke up, Johnny introduced Kerney to the people in attendance. The group included the unit production manager, set decorator, transportation captain, construction coordinator, cinematographer, the assistant director, several other lighting specialists, and Charlie Zwick, the producer. Zwick shook Kerne -

y's hand and thanked him for

his good idea. "Yeah, thanks a lot," Johnny said sarcastically, after Zwick left the building. "Come on, Johnny," Kerney said. "It was apparent that the director had already made up his mind to change the ending before I spoke up." "You don't get it," Johnny snapped. -

Laser Cutting Work Station (LCWS):

"I'm trying to build public interest in rodeoing with this movie. Get people excited about the sport, make it a major ticket draw. Now that's not going to happen. Instead, filmgoers are just gonna see w - hat they think are a bunch of neat horseback and cowboy stunts as part of a brawl." Kerney pushed open the door and stepped outside. "I wasn't trying to thwart you." Johnny took the cell phone off his

belt and flipped it open.

- "It sure felt that way. I've got some phone calls to make. I'll see you

- later." Jolvmy hurried across the parking lot with the cell phone

- planted in his ear. Kerney decide

- d to let Johnny ch

- ill out before go

- Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer

- ing to the apartment. He didn't want to face a contentious evening with Johnny ragging on him about no

t gettin Chemistry Laboratories work closely with the other divisions of g his way. It was a good two hours be, fore

dinner. He decided to drive to the smelter to take a

look at the place that had inspired Malcolm Usher to

change the script. Besides, he wanted to see the Star

of the North that Officer Sapian had told him about.

The paved road from Playas to the copper smelter

paralleled a railroad spur that connected with the

main train line

east of Lordsburg, a windblown

desert town on Interstate 10 that served as the seat

of government for Hidalgo County.

The valley widened a bit as Kerney headed south,

deep into the Bootheel. To the west the Animas

Mountains cut a broad,